Who Says the Blockbuster is Dead?

At DCAT 2016, IMS Health economist Graham Lewis noted that pharma is reliving trends last seen in the 1980s. Despite value-based medicine, he said, the blockbuster model is alive and well.

The Drug, Chemical, and Allied Trade (DCAT) Association’s annual meeting and conference program in March 2016, featured the usual look at trends driving global markets and innovation. Speakers examined macroeconomics, R&D focus, and the impact that value-based medicine, pricing, and payer models can be expected to have on drug development and manufacturing.

Leading speakers on the program was IMS Health’s economist Graham Lewis, who channeled Christopher Lloyd’s character, Dr. Emmett Brown, from the film “Back to the Future,” with his talk. It was entitled “Confounding expectations: How pharma reinvented innovation and turned the world on its head.”

Lewis challenged analysts who pronounced that pharma’s blockbuster business model was dead. High-volume products remain important to the top 20 pharma companies, he said, and last year, just over half of the industry’s sales came from blockbusters.

“Many of you depend on scale, and revenues from scale,” he told the audience. Of the new chemical entities (NCEs) introduced between 2010 and 2014, he said, eight products were worth more than a billion dollars and one, more than 12 billion dollars.

Five of the top 10 pharmaceutical companies currently derive more than 30% of their revenue from one therapy area, he said, with 15% of Pfizer’s revenues from central nervous system (CNS) therapies, 21% of Novartis’ revenues from oncologics, 34% of Sanofi’s revenues from diabetes, and 20% of Teva’s revenues from therapies for multiple sclerosis (MS).

Lewis also questioned whether value-based medicine is limiting innovation. Citing Sovaldi (Gilead) as a case in point, and “only the first of several potential tsunamis to affect the market,” he noted that “The market will accept higher prices if the innovation is there.”

Overall, the global pharmaceuticals market is growing by 4–7% overall, and should reach $1.3 trillion in 2019, Lewis says.

The number of new active substances has been increasing since 1996, and will reach record levels between 2016 and 2020, Lewis said, with 225 expected to be launched between 2016 and 2020, a return to higher levels seen from 1996 to 2000, when 223 were launched, and a dramatic increase from levels in 2006–2010, when 146 were launched.

Currently Lewis said, the US dominates launch of NCEs; between 2010 and 2014, pharmaceutical companies in the US launched 121 new chemical entities, with German companies launching 92, UK firms 83, and Japanese companies 67.

Three-quarters of new drugs focus on five therapeutic areas: hepatitis, diabetes, oncology, anticoagulants, and autoimmune therapies. As payers try to reduce drug spending and make it more effective, they are also having a problem finding money for all the areas where innovation is coming through,” Lewis said.

For manufacturers, in turn, value-based medicine has made it more difficult to have a sustainable innovation model, Lewis said, and companies are feeling the pressure. Some major employers, such as Coca-Cola, have launched pilot programs designed to reduce spending on prescription drugs.

Intensifying the value-based medicine debate, especially in the oncology field, have been independent groups such as:

- The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), which has developed benchmarks for value-based pricing for expensive drugs (and recently released

a white paper summarizing pricing approaches.

- Memorial Sloan Kettering, whose

Abacus program proposes that cancer drugs be priced based on efficacy, toxicity, novelty, R&D cost, disease rarity and disease burden

- The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), which has introduced the

quality-adjusted life year (QALY) as a means of measuring a drug's value.

One of the most dramatic changes in recent years has been the growth of developed markets. “Resurgence of US growth (which in 2012, had been negative, Lewis said, for the first time in IMS’ 57-year history) is the most significant event of this decade,” Lewis said. The US should account for 45% of global growth through 2020, he said, and remain a top market for innovators, growing by more than 7% per year over the next five years, Lewis said.

Growth in “pharmerging” markets, meanwhile, is slipping, he said. Ten to 15 years ago, many top pharma company CEOs saw all the growth in emerging markets and expected it to remain there. Over the past five years, Chinese annual pharma market growth, for example, has fallen from 17% to between 6% and 9%, Lewis says. It is likely to stay at these levels over the next five years, he adds, while the government sorts out problems such as its huge national debt.

Pharmaceutical market growth in Brazil, meanwhile, has dropped from 12% per year to 2% per year, he said. Political, economic, and social problems have increased instability in the country and made it more difficult to forecast growth there, he added.

Major companies have slowed or stopped investing in emerging markets, Lewis said, and some are asking whether they need to form new alliances in order to succeed, since local and regional players seem to be faring better than multinational players.

Nevertheless, these markets remain extremely important, and should emerge stronger from their current challenges. By 2020, Lewis projects, China will account for 12% of the market, as much as the top five European markets. It will be the second largest pharmaceutical market in the world, followed by Japan.

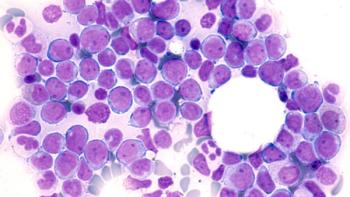

Not only specialties, but biologics are becoming a more significant part of the pipeline, and large molecule drugs account for roughly 24% of industry sales. In 2020, by which time many key biologics will lose patent protection, the top 10 pharmaceuticals will likely be biologics, Lewis said.

Large molecules make up the following percentages of each phase:

- Preclinical 48%

- Phase I 45%

- Phase II 44%

- Phase III 39%

- Pre-reg/reg 35%

US biosimilar players are leading in drug development, Lewis said, but markets such as South Korea are becoming important, since they offer tax benefits, and financial and other support.

Oncology and autoimmune therapies are two important therapeutic areas for biosimilars. At this early stage, 35 biosimilars are in late-stage development (i.e., Phase III and Pre-Reg), Lewis said. Autoimmune therapy is generally an easier target for biosimilars, since oncology treatments usually require the use of combination drugs, he said.

Newsletter

Get the essential updates shaping the future of pharma manufacturing and compliance—subscribe today to Pharmaceutical Technology and never miss a breakthrough.