Unpacking Amgen v. Sanofi

Exploring the state of pharma patents following the Supreme Court’s Amgen v. Sanofi decision.

The 2023 Amgen v. Sanofi Supreme Court case caught the interest of many members of the pharma industry due to its broad implications for the future of patent law in the industry. Following the court ruling in favor of Sanofi, BioPharm International® spoke with Kisuk Lee, principal at Harness IP, a law firm specializing in intellectual property law, on the Court’s decision and its implications for the life sciences industry.

The supreme court’s ruling

BioPharm: In the Amgen vs. Sanofi case, what exactly was at stake?

Lee (Harness IP): This is actually a huge-stakes case because this case discusses one of the most important requirements—patent protection. Basically, there are four major requirements: patent eligibility, novelty, non-obviousness, and written description, which includes enablement. The patent enablement requirement essentially states that the patent specification must provide descriptions that enables the claimed invention. In other words, the patent specification must describe how to make and use the claimed invention. In this case the issue was, how much information is enough to enable full scope of the claimed invention?

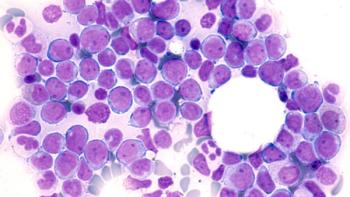

In the Amgen v. Sanofi case, Amgen’s patent is directed to an antibody which is really broad. It simply claims an antibody binding to a certain antigen to treat a certain disease. The antibody itself is not structurally defined—just any antibody binding to antigen X, that’s the breadth of Amgen’s patent claim. Additionally, the original Amgen specification provided about 28 specific antibody examples, sequence information, and very detailed descriptions about how to make and use the invention.

But the problem is that the claimed invention was rather broad. So that was the issue, whether the information included in Amgen’s patent specification was enough to enable the full scope of Amgen’s broadest claim. The Supreme Court’s view was ultimately that the claim was too broad, resulting in a ruling that says the original patent specification should provide description enabling full scope of the claimed invention. This is a high burden.

In the past, the Amgen patent claim was definitely patentable and there was no issue about enabling disclosure. Typically, in the pharma world, the most important part is finding the target protein, which leads to treatment of certain diseases. If we want to treat brain cancer, then the most important part is to identify the key protein involved in this disease. That correlation, the inhibiting protein X thereby treating brain cancer, that’s the most important part of the discovery.

But according to the Supreme Court ruling, you cannot get that broad protection because you only identified one or two specific antibodies, enabling the claimed invention. So now the outcome is you cannot get that broad protection and only an extremely limited, narrow scope of protection even if you discovered a breakthrough scientific principle, such as inhibiting the hypothetical antigen X for treating brain cancer.

Effect on research

BioPharm: How will this impact pharma researchers going forward?

Lee (Harness IP): This is a huge burden for innovators. Amgen’s patent had a more than 400-page specification with many examples, yet that was not enough. Most patent applications are less than 100 pages; how far will they get?

Typically, patent filing is a high, heavy burden on universities and research institutes, who don’t have enough money and resources to support it. In a university setting, researchers typically try to identify the key antigen and then publish a paper, that’s it. Then they file a patent application. As a result, they only work on one or two antibodies, and they don’t have the capability of producing 30 or 40 different antibodies.

In the past, we saw a lot of mega-million licensing deals from university to industry because a university identified the breakthrough and under that protection could screen antibodies binding to antigen X to develop new treatments. But now the university can only test a specific antibody and minor variations of that discovered antibody. That’s it. This is really bad for the innovator side, especially for universities and research institutes.

On the other hand, this is great news for mid-sized and small pharma companies. Now, if Big Pharma or a university already identified the basic scientific principle, there’s only one or two antibody examples. These entities can just try to screen other antibodies that bind to the same target—that is not a patent infringement of the innovator-side patent. And they can also obtain separate patent protection because the originator’s patent only covers a narrow scope.

I always use this analogy: if your discovery is US territory, in the past you were able to get a full US territory patent but now can only get a California patent. Now, other researchers and companies can get a New York patent, an Illinois patent, a Florida patent. Basically, a floodgate opens for competitors.

[The latter scenario] is good for other researchers, and that [scenario] actually promotes competition, which may be good news for the general public because the public will get more treatments from different sources. Typically, innovations are patent only, and then patent protection, and we are just waiting for patent expiration. [After that] the generic comes in, and we make the generic version. So, generally speaking, patients have to wait until patents actually expire. But now the competitors can probably file new patent applications not covered by the originators. That may be good news for the general public, as it could lower drug prices as well.

Impact on patents

BioPharm: What kind of knock-on effects do you think this ruling might have for patent laws and any other pending enablement claims? What sort of effects are we seeing?

Lee (Harness IP): So, unfortunately, [the ruling] will affect all patents, patent applications, and patent applications to be filed. As it concerns already issued patents, in the past the patent office allowed a broad genus claim. Just like the Amgen patent, there are so many patents out there with really broad claims. That means the competitors might challenge the validity of those patents so that they can file new applications and freely exercise their own antibody. I think we will see more invalidation challenges on the generic side from small- or medium-sized companies.

Regarding pending applications, we’ll see more enablement rejections from the patent office. Because the standard is higher, many of the already filed applications don’t meet that higher standard. As a result, we’ll see more enablement rejections from the patent office.

Lastly, the applications to be filed. This is actually the most important part now as the burden for the patent applicant is really high, and [they] need to provide enabling disclosure for the full scope of the claimed invention. In the past, I advised clients that if you already synthesized 30 different antibodies or 30 different compounds falling within the scope, you don’t need to disclose everything—just provide 10 representative examples in the patent specification and keep 20 as a trade secret. You don’t need to disclose all your information.

But now it’s different. We probably need to disclose everything, yet we may not get really broad protection. That means a lot of cost and preparation [will be required] because [a company] needs to provide data and new examples; the company needs to prepare this information, and then a law firm has to write a 400–600-page patent application, which could cost double, triple, quadruple, I don’t know, but it’ll definitely be more expensive than the previous applications cost.

Additionally, if the innovator side discovered this breakthrough discovery, but only has 10 antibodies? That’s not enough to cover the entire scope. So, what’s the solution? [They will] need to file additional patent applications. To return to the prior analogy, one might initially file patent applications for the west coast, for example, California and Washington. Meanwhile, they will also need to screen new antibodies binding to that target and then file a New York application, and [following that] an east coast application or Midwest application.

[Innovators will] have to file more applications to cover a broad scope. That’s a higher cost because of filing costs, preparation costs, prosecution costs, and maintenance costs. I think it’s really bad news for innovators. Universities in particular don’t have money—their antibody budget is quite limited—so I don’t think university research institutes can file five or six different patent applications for one discovery. That’s really a sad outcome for those small players.

Pharma’s next moves

BioPharm: What do you think companies should be doing now, other than just spending more money and filing more of these enablement requirements?

Lee (Harness IP): Unfortunately, there’s not much wiggle room. The Supreme Court ruling is quite simple. You need to provide enabling disclosure for the full scope. So, planning ahead may be useful. Now we know that it is useless to file an application with a US territory claim with only one or two examples. If you have only California examples and just start with California territory, and if the claim is covering California only and [the innovator] has three or four examples falling within the scope, then that’s fine. That may be a good approach because [the innovator] can later file applications for other areas.

If [an innovator] were to use the past approach of just filing the hypothetical US territory claim and then seeing what happens? Then they cannot file a follow-on application directed to New York or Midwest because they have already disclosed the full scope. The really important requirement for patent protection is novelty and non-obviousness. Once their US territory is disclosed in the original specification, then it would be supremely difficult to file an application later covering New York or Florida. If, however, [the innovator] focuses on one area, such as the west coast application, first, then the Midwest application is new, and the east coast application is new, because the earlier publication is limited to the west coast. Planning ahead, identifying the patentable scope, and just filing an application covering that patent scope—then later filing multiple applications covering other

areas—may be a strategy.

Future pharma research

BioPharm: Do you think this will affect how research is done in pharma? Are certain types of molecules going to be prioritized and or certain types of research?

Lee (Harness IP): Generally speaking, the pharma industry’s two big areas are the traditional small-molecule drugs and biologics. Small molecules will be okay, in my opinion, because the broad invention is typically defined by a structure. When researchers discover a new molecule, they have to provide a generic, that is, the chemical structure scaffold and then possible substitution. In most cases, chemical inventions, such as small-molecule drug inventions, are defined by structure.

But the biologics industry is different. Innovators need to identify a pathway as well as the certain messenger molecules involved in that pathway. Then they have to show what happens when that pathway is inhibited to demonstrate how that kind of modulation is necessary for biologic inventions. Thus, functional language and broad coverage is necessary. That was actually the problem with Amgen—there’s no other way to cover their idea with structured terms. Someone can provide a thousand different antibodies for this discovery, which means the biologics area is really affected by this Supreme Court decision.

About the author

Grant Playter is associate editor for BioPharm International.

Newsletter

Get the essential updates shaping the future of pharma manufacturing and compliance—subscribe today to Pharmaceutical Technology and never miss a breakthrough.